In an audio world dominated by digital wizardry and high-efficiency Class D amplifiers with three- or four-digit power outputs, high-end manufacturer Audio Note is something of an anomaly. Here, they hold on to technologies that had their heyday in the middle of the last century. Old-fashioned? No, simply because they believe the classic design principles are sonically superior to the newer ones.

It’s primarily about valves. All Audio Notes amplifiers, CD players and DACs use radio valves for amplification. And preferably triode valves, which are considered to have the warmest and most harmonic sound. Other hallmarks are transformer coupling and the use of silver.

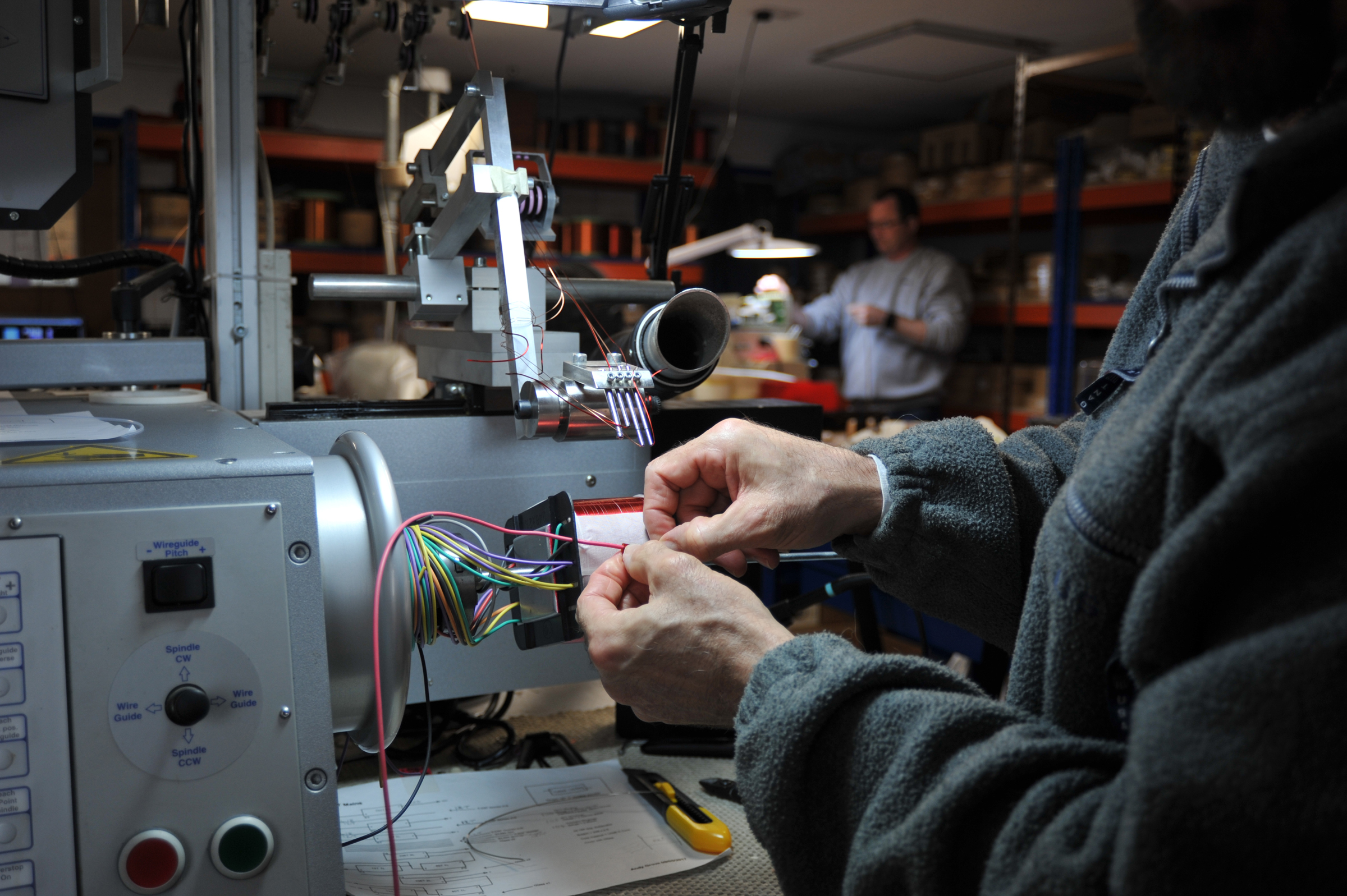

At the factory in Sussex in southern England, the equipment – both the most expensive and the less costly – is built by hand. The models we see on the tour are all pre-ordered. They do not build to stock. On the other hand, Audio Note has a large stock of components, most of which are either custom-made or antique.

A mysterious cable came from Japan

Audio Note UK is a British company, but it began in 1980s Copenhagen, where Peter Qvortrup was the owner of hi-fi shop Audio Consult. One day, a metre of signal cable was sent to him by a Japanese engineer called Hiroyasu Kondo.

“Back then, cables were just something you used to connect your equipment together. The cables that came in the box were used. No one made or sold special cables.”

The Kondo cable was inserted between the preamplifier and the power amplifier, and they listened. “It all went up a level!” recalls Peter Qvortrup, who that same evening sold the cable to a customer who had attended the listening session in the store – and who just had to own the Japanese signal cable. The customer paid well, so the deal was made, and Peter Qvortrup sent a letter to Japan asking for more.

A distribution agreement was reached – via an interpreter – and Qvortrup began selling Kondo products under the Audio Note brand. At first on the Danish market, but later to a larger and larger geographical region. Until Qvortrup’s company, which in the meantime had moved to England and now also took part in the development of Audio Note products, was given distribution for the whole of the rest of the world – apart from Japan, where Kondo sold his products himself.

Silver with silver on top

One of Audio Note’s trademarks is silver. The more ambitious the components, the more places in the signal path pure silver is used (see also later on Audio Note’s level system). According to Peter Qvortrup, this just makes for such a cleaner sound that it’s worth the expense.

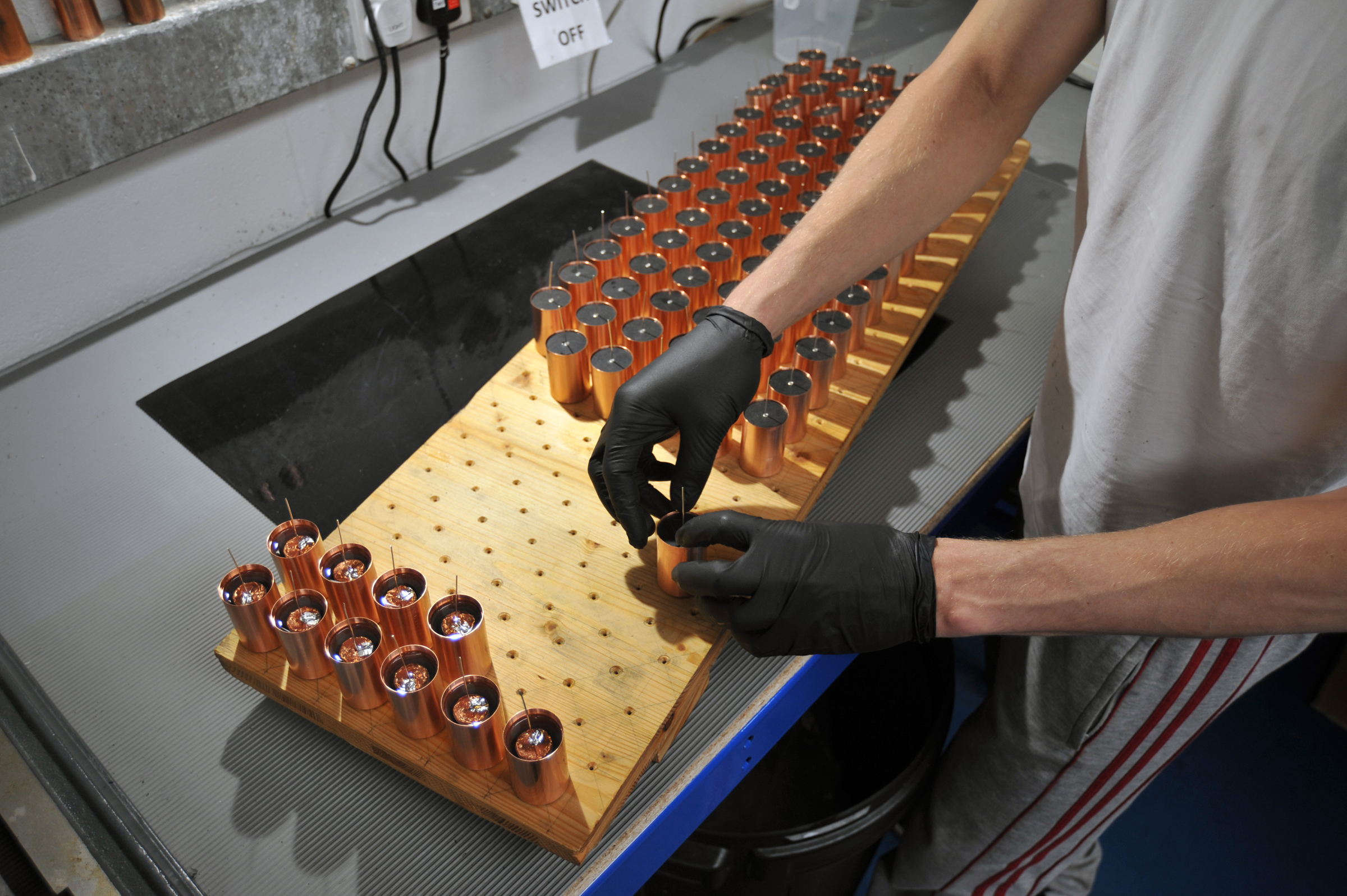

That silver is used in the cables almost goes without saying. But even component leads, the foil in capacitors, crossover coils, speaker voice coils and even the wire in transformers are silver when we get up to the more expensive luxury models.

“It actually makes an audible difference that the transfer transformers are wound with silver wire, even though they measure the same,” says Peter Qvortrup. “The only difference we’ve been able to measure between silver and copper in the transformers is that the magnetic field lines are a little bit closer around the core. But it sounds different.”

Components like these are not found on the shelves of the nearest electronics store, but must either be made to order or manufactured in-house. On the tour, we see how transformers are wound and capacitors made by hand.

Another speciality is resistors. Most resistors in electronic equipment are made of metal foil or are wire wound, in both cases with a nickel-chromium alloy. But Audio Note has instead chosen resistors with a film of tantalum. Again, because it sounds better.

As the manufacturer, Shinkoh, had abandoned production and scrapped its machines, Peter Qvortrup had to find another company in Japan that produced resistors, called HDK. It took over 15 years to persuade them to produce non-magnetic resistors with silver and tantalum.

Developing a silver alloy tough enough to be used for the resistor leads and the small metal caps that terminate the resistor body was a different and costly matter, again taking three years. A single silver-tantalum resistor retails for £32 (about €38). But then it should also have an extraordinarily more homogeneous and detailed sound without any harshness!

Transformers

Since all Audio Notes amplifiers are valve amplifiers, transformers are necessarily used in the output stage to adapt the high-voltage signal to drive a speaker. But transformers are used throughout the company’s devices, rather than other components, such as for impedance matching on inputs and outputs. There is also a transformer in the RIAA circuit on the turntable input.

“The transformer is a virtual component. If it is correctly dimensioned, it has no effect on the signal other than transforming between voltage and current,” says Peter Qvortrup.

In Peter Qvortrup’s own system, no less than 11 transformers are included in the signal path when listening to CDs. In contrast, the extreme Gaku-On power amplifier contains, in addition to three transformers, only four other components in the signal path: two triode valves and two resistors! No capacitors. The single-ended triode amplifier with no negative feedback delivers 45 watts of pure Class A power.

New Old Stock

Audio Note tube amplifiers are built on valves that were classics even in the middle of the last century: 211, 300B and 2A3. The valves are still made, but production is small, prices astronomical and quality varying. This is where Peter Qvortrup heads to his valve warehouse …

Much of the factory’s space (plus a couple of remote warehouses) is used for the company’s treasure trove of “New Old Stock” components. That is, components made decades ago but never used. Here, pallet after pallet of coveted valves are ready to be used in amplifiers.

“Some of these are crazy expensive today. Fortunately, I didn’t pay that much for them back then,” says Peter Qvortrup with a satisfied smile.

Tiered high-end

Audio Note operates with a system of levels – Performance levels – by which they classify their equipment. The scale goes from 0 to 6. The higher the level, the more extreme (and expensive) the component selection. According to Peter Qvortrup, it’s all about putting the effort into system, so that you get audio value for your investment:

“As a rule of thumb, you should build your system according to the technology level of the amplifier. The other components should be at most one level above or two below the amplifier’s level.”

The level system is both a buying guide and an upgrade plan. Some of the company’s models can be bought in several level variants, and some – including the speakers – can be upgraded later with more advanced parts, with cables, components and voice coils finished in silver.

Comparison by contrast

When listening to a piece of hi-fi, finding a neutral point of reference – a yardstick – to judge quality is an inherent problem. It’s both about having a known point of comparison in the form of a reference system and about assessing whether what’s being tested sounds better, more accurate – or just different.

Peter Qvortrup advocates a principle called “comparison by contrast”:

“If the definition of hi-fi is to reproduce the recording as faithfully as possible, then the best system must be the one where you can hear the difference between the albums most clearly,” he says. “If all records sound the same, it’s the sound of the system we’re listening to – not the recording. The more different they sound, the less of a fingerprint the system has left on the sound.”

Logically, this method can also be applied to individual components of the system. If replacing a device in the chain makes the difference between individual recordings stand out more clearly, that must be an improvement.

From Caruso to Nightwish

There is plenty of opportunity to experience this difference and contrast when Peter Qvortrup delves into his thousand-strong record collection. During the visit, we listen to classical orchestral music, Dutch noise-electronica, Finnish symphonic heavy metal and American 50s calypso. To name just a few of the extremes.

Peter Qvortrup talks enthusiastically about the finer points of each record – and their background (he knows many of the performers as customers of the shop). Transfers of hundred-year-old gramophone records by Enrico Caruso are also played. And it’s clear that Peter is fond of the many and varied records he pulls from the floor-to-ceiling shelves in the music room. Not all recordings are faultless, for natural reasons, but the important thing is that they are interesting.

“I once played a recording from 1940 at a trade fair and read online afterwards that our system had been ‘the noisiest on the show’. Bloody hell, there’s noise on a recording that’s 70 years old! But the person had only stuck their head in for a moment without knowing what they were hearing.”

There’s no doubt that the system is top class. And the characteristics of the many recordings are crystal clear. I’m impressed, for example, by the way reflections from the back walls of the concert hall can be distinguished. On a classic recording, by the way, made with equipment from Audio Note. But most of the time, it’s about hanging on for the whirlwind rollercoaster ride through genres and time periods.

And let’s once and for all hammer a stake through the myth that single-ended triode amps can only play quietly and nicely. When Peter turns up Nightwish, Noisia and Tool, the sound pressure is overwhelming.

One million!

The system being played on is, of course, Audio Note through and through. From the pickup to the speakers. And just as obviously, it’s the top models that are being played on. A system with a retail price of around one million euros! That sounds like an exorbitant amount of money – especially when we’re talking about amplifier power of 2 x 45 watts (Gaku-On) and two-way speakers with 8-inch woofers (E Sogon).

“It’s a lot of money, but the parts are also really expensive. For example, 15 kilos of pure silver go into the crossover in each speaker!”

One name – two companies

Today there is not one, but two companies with the name Audio Note. The British one, owned by Peter Qvortrup, and a Japanese one, run by descendants of Hiroyasu Kondo. But they are two entirely separate entities, even if several of the two companies’ products share the same name.

After many years of steady growth, Kondo and Qvortrup broke up in 1998.

“Our main market was in the Far East. In May-June 1997, a huge currency crisis started in Thailand and spread all over the Far East. This led to a huge drop in sales of Japanese products. Mr Kondo would not accept reduced orders, but simply said ‘I make, you buy!’, which is not possible if you do not have customers who are willing to buy. That’s why Kondo-san cancelled our distribution agreement in February 1998,” says Peter Qvortrup.

Eventually, the partners broke up. Kondo, who had originally started Audio Note, wanted the rights to use the name worldwide.

“I told Kondo that of course he could have the name – as long as he paid me what it had cost to register the trademark globally. But he wouldn’t, so we ended up keeping the rights to Audio Note.”